Frames of Reality: The Interplay of Causality and Temporal Perception in Defining Knowledge

On Causality as the Defining Principle of All Knowledge and on the Subjective Nature of All Knowledge.

If I throw a die or think of a random number and then tell you what it is, I doubt that would you consider this information “knowledge” (unless your goal is to argue with me). This is because such data, when considered in isolation, is highly unlikely to be relevant to anything that will happen in the future. So, we can define knowledge as “information that is relevant in the future, i.e., that can be used to predict it.” Thus, the concept of knowledge is deeply intertwined with the concept of time. So, to understand what knowledge is, we must understand what time is. Indeed, to have a concept of the future at all, we must be able to perceive time. So, let’s explore how we do that. There are many ways to approach this question, but I often find it benefitial to think about things in terms of input and output:

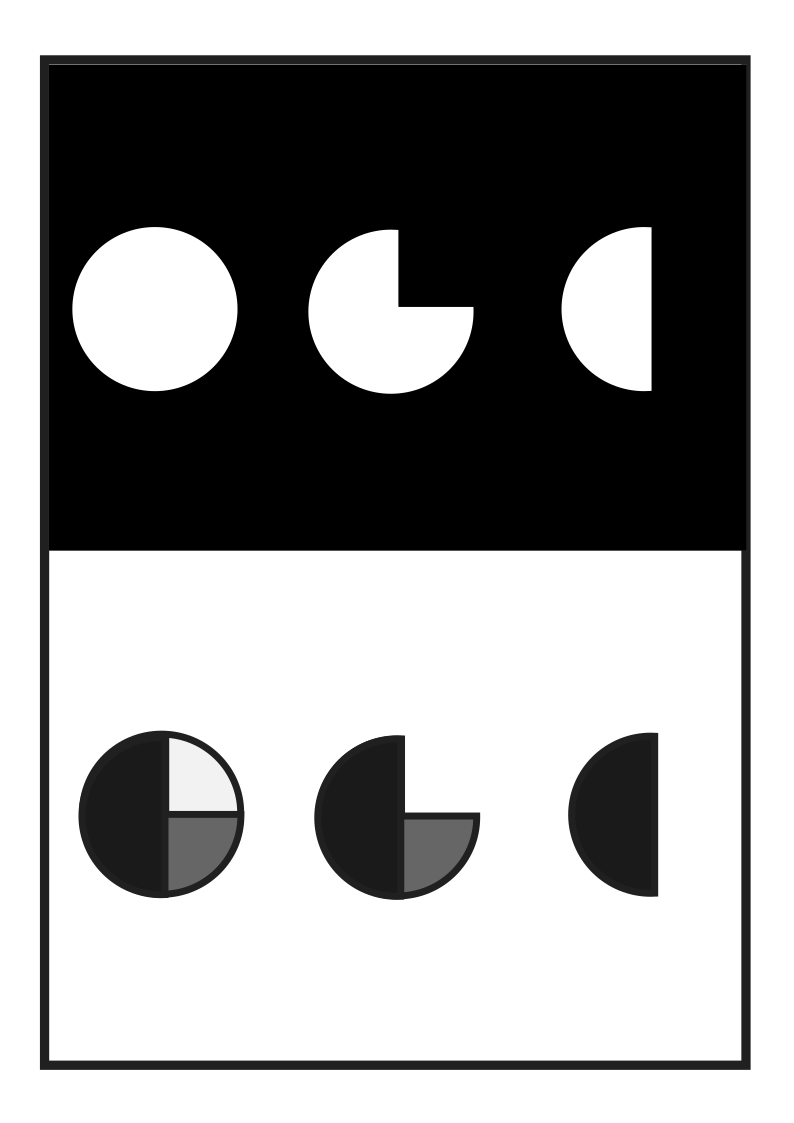

- We can view the input that our brain receives, which forms our perception of time and continuity, as a collection of frames – pictures of different states of reality. These frames are then somehow unified in the output.

In other words, the mystery of time can be reduced to the following riddle: We have two pictures, and we have to identify the elements of the first one in the second one, like a reverse version of the “Find the Ten Differences” game. This might sound simple, but it is far from it.

- For the perception of time to be realized (and for knowledge to be created), the list of frames must be interpreted as signifying some form of change from one state to another—such as a change in position (motion), shape, or color.

- If all the frames are all alike(e.g., if you are staring at a blank wall), you would not be able to perceive change (and thus, time).

- But, if the frames are all entirely different, don’t have anything to do with one another, you also wouldn’t be able to perceive change.

To perceive change, then, we must be able to interpret the frames in such a way that there is an aspect of them which is different for each frame but at the same time stays the same for all of them. This requires us to postulate the identity of objects and events (we can view objects as just prolonged events).

- The basic form of identity of events and objects (where objects are merely collections of events) is grounded in the concept of causality. When observing event

Ain one frame followed by eventBin the next, we presume thatA ⇒ B(i.e.,Bis caused byA).

This implies that identity is just a manifestation of causality — they are basically the same thing. For instance, if I see an object on my desk, and then I see a similar object in the next moment, I assume it is the same object, meaning that the object’s presence at time x causes its presence at time x + 1.

There are other ways for defining the identity of objects (we can say, for example, for example, that an object is the same only if it is composed of the same atoms), but this is the main way that identity is perceived by people in practice. A ship that has had all its parts replaced over time is still considered the same ship, even though its material composition has changed.

However, if we think more about the ship, we realize that identity, defined in this way, is not absolute.

- Causality is in the eye of the beholder.

A ⇒ Bis not an objective fact about the world but a mental image. This is becauseBis partly defined by its internal characteristics and partly by being “the thing that follows fromA(ifBoccurs withoutAoccurring first, (e.g. if there is thunder without lightning) to what extend would it still beB?).” Similarly,Ais partly defined as the thing that precedesB.

This is the central proposition of this text. Imagine we know that A ⇒ B and we observe A and then another event, B', that resembles B but also differs in some characteristics (note that this is not just a thought experiment but a general description of perception, as all events are unique).

In this situation, we have two choices:

-

We may assume that

Ais not actuallyAbut some other eventA', thus discovering a new fact:A' ⇒ B'. -

Or we may assume that since it follows from

A,B'must be some variant ofB, thereby expanding the ruleA ⇒ Bto include this new characteristics ofB.

The former kind of thinking is called “empirical”, the latter one — “dogmatic”. When thinking empirically we obtain new information about the world, while dogmatic thinking allows us to use this information to make predictions. These two approaches complement each other, like input and output, like question and answer.

With this, we establish that dogmas like A ⇒ B are not truths but rules for organizing information. We might naively consider them true because they “work” — they help us achieve goals or avoid trouble — but in reality, they are neither true nor false. Instances that follow a rule might only follow it by accident or because we perceive them that way. Instances that don’t follow a given rule are simply not instances of that rule. No rule is inherently true or false, and so no proposition is true or false either.

By the same token, we may naively think of the causality maxim (of A ⇒ B) as true (true as in “valid law of nature”, let’s say), because when we perceive A, followed by B, and it is easier to explain that by postulating causality than to just say it happens by accident (Occam’s razor). This may lead us to believe that causality is some kind of law that exist in the world, or rather a meta-law, which implies the existence of all kinds of other laws. In this case, we would be overlooking the following:

Bis not a specific state of affairs but a mental image, a pattern we begin to search for based on our prior knowledge ofA ⇒ B.

We search for B and often find it, even when there are no perfect candidates. If we already believe in A ⇒ B, we will see B wherever we see A. In this case, we say that someone sees B even when it is not really there, but the fact of the matter is we cannot possibly see anything that is there (in the way that we see B in this example).

Causality is neither a rule nor a meta-rule, but a belief that every thinking being must hold to some extent, in order to be a thinking being at all.

The last statements may rise some objections which I will attempt to address, using the somewhat forgotten form of philosophical dialogue. Let’s imagine that the physicist Isaac Newton, (who pioneered the modern scientific method) had a chat with the philosopher David Hume (who challenged the principles on which this method is based).

Hume and Newton

Hume: Causality is not a quality of the world, but merely a belief. It is a very general belief and one that every thinking being should hold to some extent, but still, it is just a belief.

Newton: That is nonsense. The world clearly adheres to certain laws, independent of our observation. This means causality is a characteristic of the world itself i.e. a law.

Hume: OK, let’s say you are right. If causality were a law, there ought to be a way to test it, as we do with all other scientific laws, right?

Newton: Of course, and as a matter of fact, we do that often. All scientific theories are based on the causality maxim. A scientific theory is nothing but the assumption that a statement of the form A ⇒ B is true. We then test this theory by conducting experiments where we make A happen repeatedly and see if B follows. So, besides testing a given theory, every scientific experiment also tests whether causality itself works.

Hume: This is true, but many, if not most, experiments fail, at least to some extent. Doesn’t this suggest that causality itself fails?

Newton: The only reason why experiments fail is that we don’t yet know enough to conduct them properly. Blaming causality for our failure is ridiculous. If our theory is exactly right, it will produce the expected outcome every single time.

Hume: That sounds too theoretical. Can you give a concrete example of an experiment that always gets the expected outcome? If you do, you win.

Newton: Very well. Let’s consider this very simple experiment: a pistol is aimed at a window. The trigger is pulled, and the window shatters.

Hume: But what if there’s no bullet in the pistol? Or if the pistol is broken?

Newton: OK, let’s assume a bullet is necessarily fired, and the aim isn’t off. Then the glass breaks.

Hume: What if the window already has a hole?

Newton: No, there isn’t. The bullet hits the glass, okay?

Hume: Alright, but how fast is the bullet moving?

Newton: Let’s say it hits the glass with sufficient speed.

Hume: Sufficient for what?

Newton: Sufficient to break it.

Hume: See what you did there? You defined the situation so that the effect is embedded in the setup.

Newton: So, you’re saying the effect can be embedded in the setup? That sounds quite objective — not really a belief.

Hume: Look, there may be possible cases where you will be able to guess whether the glass gets broken, but this does not make the general principle true. Because there is no general principle, in a first place, only a mental image and situations which remind you of the mental image.

References

-

Dogmatism and Empiricism are two schools of medicine in ancient Greece and Rome. Dogmatism was pretty much lame, but Empiricism, also known as Pyrrhonism (and later skepticism), is the origin of many of the ideas that I discuss here.

-

The definition of identity and the example with the ship are from the treatise of human nature by David Hume.