Dogmatism Through the Lens of Memory: The Unreliability of Past Events in Shaping Our Worldview

On the Ability to Memorize and How Our Thinking Becomes More Dogmatic Over Time Due to Mental Images and Goals Mistaken for the Actual World

Practitioners of mnemonics have long understood that the easiest way to remember a collection of unconnected pieces of information is to just make up some connections between them. This is because our brains cannot capture raw perception data — they can only capture mental images and causal connections i.e. we only remember events that are connected with one another.

- Because we necessarily see them as connected, all events that we remember form a structure known as a causal chain.

An event that has nothing to do with our causal chain is simply not perceived by us (or, if perceived, it is not remembered even for a second). In many ways, placing the event in the causal chain is perception itself.

However, since humans have only one causal chain—i.e., we do not have multiple ways to perceive a given set of events that we can switch between—placing an event on the causal chain also means replacing it with a mental image.

- Due to the way memories work, mental images reinforce themselves over time — having the image of

A ⇒ Bin our minds, we would seeA-s andB-s all over the place.

One of the most significant biases in our perception of time, which we’ve already discussed, is our inability to distinguish between the mental images representing the world (M) and the world itself (W). This bias leads us to believe that our perceptions reflect the state of affairs when, in fact, they are merely a record of our mental images. Memories contribute heavily to this bias, as they can amplify it indefinitely: when we perceive a given “frame,” the memory of it is rich in sensory (empirical) data, which we can analyze and interpret. But once we perceive the next frame, many aspects of the previous one are compressed, leaving only those details that provide context for the next frame. Then, when a third frame is perceived, the first two are compressed further, retaining only what’s useful for interpreting the third. The problem is that we cannot know which aspects will actually be useful for future context.

Like causality, we naively view our memories as true representations of reality because they “work”—i.e., they have a good success rate at predicting future events. But, (as with any mental image), we lack a clear criterion for what it means for memories to “work”. Like all mental images, memories represent an interpretation of reality, but they are also immutable. Once a past event is categorized under a mental image (say, A), it cannot be reinterpreted as anything other than A, even if we later adopt better or more accurate mental images for similar events.

- The interpretation of past events cannot be modified, and different interpretations cannot be compared, as the raw perceptual data is lost once details of the event are forgotten. If we label an event

Aat timeT1, and later, at timeT2, we “upgrade” our understanding and categorize similar events asA'(which we might consider more accurate), this upgraded view will affect future events but not the event at timeT1, which remainsA. Without the raw data, we have no way to know whether it was trulyA'all along.

In other words, past events we remember are mere projections of the mental images we used at the time of perception. They are as unstable and subject to change as our future projections.

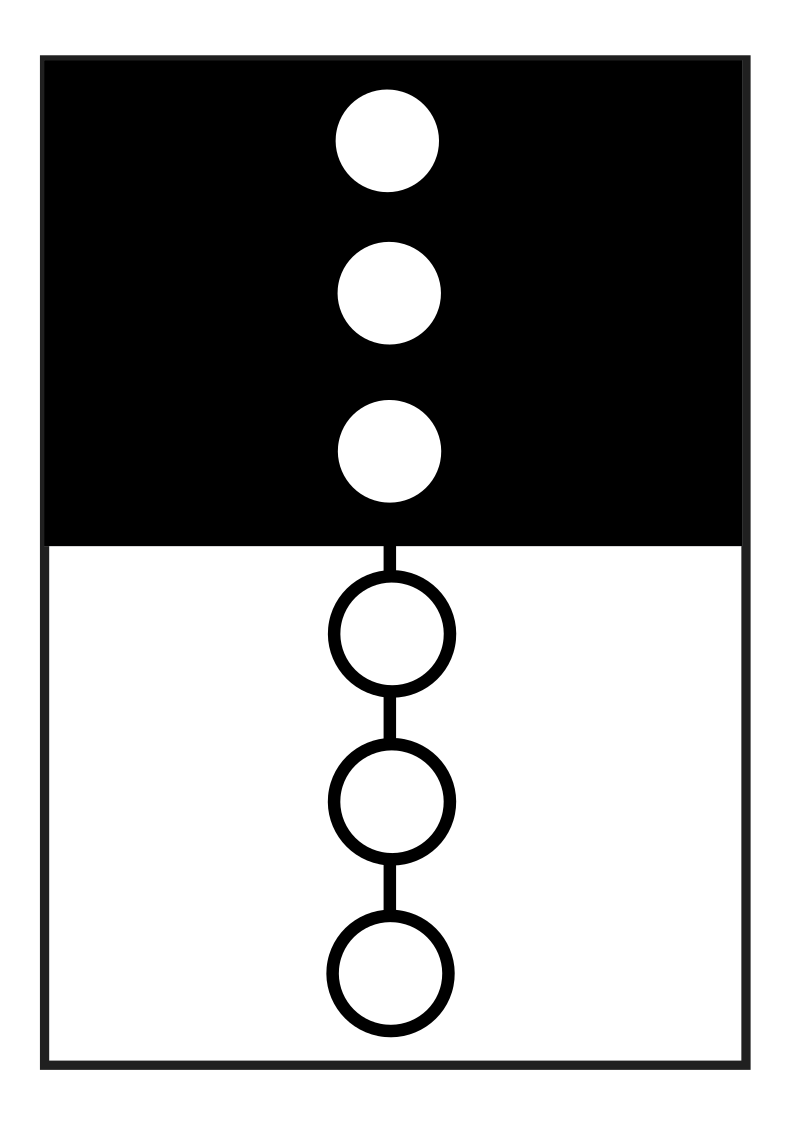

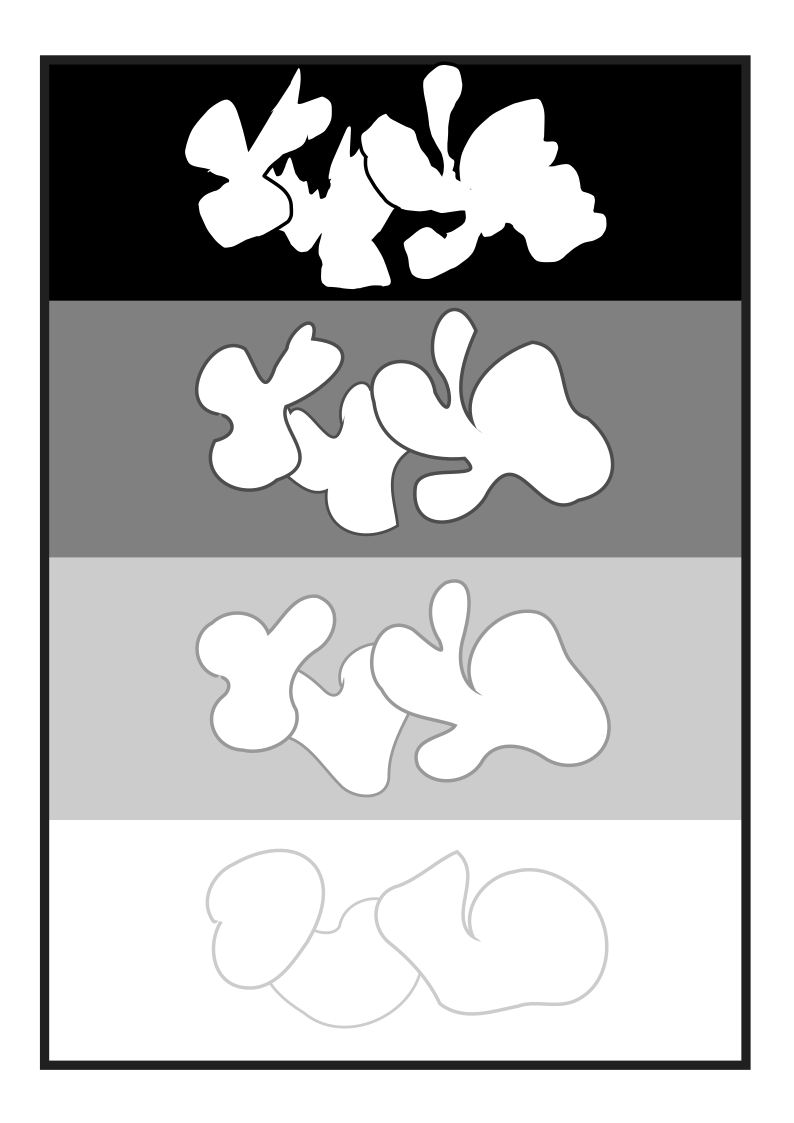

Additionally, events within the causal chain are further compressed as more structure is imposed over time. For example, if I remember going to school yesterday, I don’t remember every detail—locking the door, waiting for the bus, etc.—because much of that is implicit (some computer compression algorithms are based on the same principle). This compression intensifies with time. Ten years from graduating, I don’t remember any specific day at school, only an abstract image of the time spent there. However, this compression is “lossy”, meaning that over time, our memories become more abstract, and we recall fewer concrete details about what actually happened, focusing instead on mental images. This process is sometimes called “stylization” (a term from visual arts): an image is non-stylized when it reflects perceptual data (like a photorealistic painting) and stylized when it reflects ideas (like a road sign).

- Stylization works in the following way:

- We recall an event or a chain of events from our memory.

- We interpret it.

- We save the interpretation of the memory in the place of the original memory

In truth, this isn’t entirely accurate way to put it, as the memory was an interpretation all along, just less stylized. Memories are interpretations of interpretations of interpretations.

The more distant an event, the more abstract and stylized it becomes, i.e. it is more connected to the mental images we used at the time of perception. Consequently, we cannot create any new mental images from our memories, only extrapolate from the ones we already have. This is why older people tend to be more dogmatic than younger people—over time, we accumulate more mental images, and thus perceive less. The only way to avoid this is to have no memories at all.

The Default Interpretation

Memories are an unreliable source for understanding reality, a fact we should account for when drawing conclusions. However, as we will see, this isn’t our typical stance, since many of these images are deeply embedded in our minds.

Every set of events allows for many interpretations, an interpretation being the simplification that enables us to process and store the events in our brains. A valuable skill, that I discuss here, is the ability to “switch” between interpretations—to see a set of events from a new perspective, for example, realizing that something once perceived as beneficial is actually harmful, or even seeing ourselves in a new light. This skill is a prerequisite of all new ideas, it is thinking itself.

However, the more abstract (stylized) a concept, memory, or mental image, the harder it is to modify its interpretation, as it is already interpreted when stored as a memory (i.e. it is already connected to a particular interpretation). To reuse the previous example, if we believed that a given action was beneficial for us, memories of performing that action would be happy ones (even if the experience itself wasn’t entirely happy). Thus, relying on memories can prevent us from reconciling our stance. This is why recordings or other people’s accounts of past events can help shift our perception better than memories alone.

Moreover, mental images reinforce themselves through memories. If the better part of our memories are recorded with a particular interpretation, than that interpretation will eventually dominate our consciousness. For this reason, it makes sense to talk about the default interpretation—the one through which a person sees the world, connecting all experiences into a coherent whole, and which is rarely questioned because it essentially becomes the self.

This default interpretation is closely tied to the concept of the self.

References

- Nassim Taleb often explores the human inability to see and account for uncertainty.

- Marshall McLuhan discusses the cultural impact on our worldview in his book Understanding Media.